Author: Benjamin Zenner

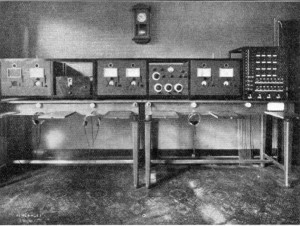

In the early days of modern telecommunication technologies, chaos and misunderstanding reigned. Between 1850 and 1900, telegraphy spread like wildfire across the USA and various European countries. However, different technological standards were used in all these places, meaning that it was difficult and expensive to send and receive messages across national borders.

To facilitate global telecommunication, representatives of twenty countries met in Paris in 1865 and created the International Telegraphy Union (ITU). First and foremost, the ITU defined and enforced universal technological standards. This made sure that everybody was speaking the same technological language and was also playing by the same rules.

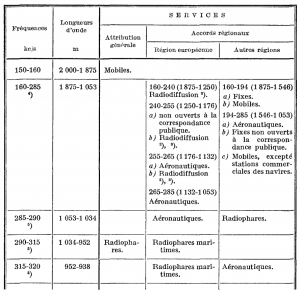

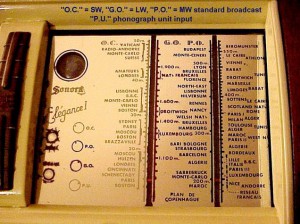

In 1932, the ITU merged with the International Radiotelegraph Union, with the ‘T’ now standing more generally for telecommunications. One of the key tasks was to define frequency plans to make sure stations did not broadcast on the same wavelengths. However, this strict system meant that stations without such licenses had to become ‘pirates’, that is to say they had to hijack frequencies that they were not allowed to use. In its early days Radio Luxembourg was such a pirate station.

Contents

Sources:

Literature:

Cowhey, Peter. “The international telecommunications regime: The political roots of regimes for high technology.” International Organization 44/2 1990: 169–199.

Lommers, Suzanne. Europe – On Air: Interwar Projects for Radio Broadcasting. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2012.

Tegge, Andreas. Die Internationale Telekommunikations-Union – Organisation und Funktion einer Weltorganisation im Wandel. Baden-Baden: Nomos, 1994.